Featured News - Current News - Archived News - News Categories

Where this new wave of 'alternative facts' came from, what its effects are, and what people can do to shield themselves from it

By Michael DePietro

Special to NFP

EXCLUSIVE: Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has been arrested after leading New York State troopers on a high-speed chase in downstate New York. The pursuit began shortly after newly released documents revealed that her campaign accepted millions of dollars in donations from ISIS. According to an anonymous but definitely real source, the former first lady was heard yelling "come and get me coppers!" shortly before careening off the road into a ditch.

Upon impact, witnesses said the trunk of Clinton's car burst open, revealing a disoriented and dehydrated Richard Simmons, who had been missing for over 48 hours.

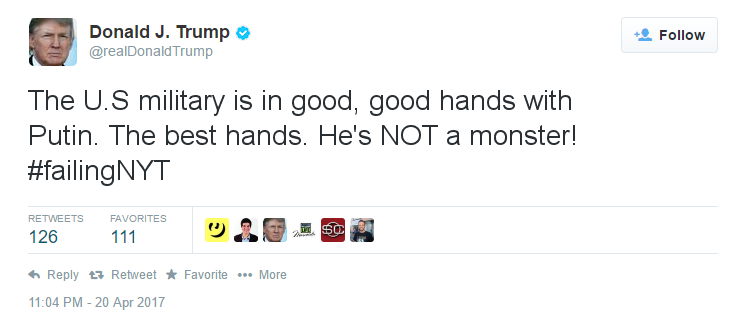

This bizarre, but definitely true story comes in only hours after the Washington Herald Tribune broke the news that President Donald Trump has signed an executive order granting full power and authority of the United States Military to close friend, Vladimir Putin. The president confirmed the decision by posting the following statement on Twitter:

The absurd reality detailed above, while wildly entertaining, is completely fictitious.

Yes, even the tweet.

To some, that probably comes as no surprise. Frighteningly, however, scores of blurry-eyed information seekers, faces lit blue from computer and cell phone screens, share and believe stories like these on social media every day. It's not just the stereotypical tin-foil-hat-wearing doomsday preppers that appear on that show, "Doomsday Preppers," either. Even bright, honest, salt-of-the-earth types can be duped. And there are very good reasons why. ...

HISTORY

Nary a day has passed since the 2016 election without various flapping-jowled pundits and politicians gurgling angrily across the television screen about fake news. The term, in general, refers to any story that spreads false or misleading information. But despite its sudden prevalence, fake news is a not some new invention.

Until recently, over-the-top stories like the ones above would have been written off as "tabloid fodder," the stuff of which was usually found in those obscure publications that seem to exist only in supermarket checkout lines.

In between issues of Soap Opera Digest and the iconic leer of Weekly World News' "Bat Boy," one would likely find scandalous headlines like "Hillary Clinton Hooked On Pills!" from Globe, or "Supreme Court Justice Scalia — Murdered By A Hooker" from its sister publication, the National Enquirer.

For many in the general public, these stories usually garnered little more than a curious glance, a whimsical shake of the head and a brief chuckle. Then the groceries would be stacked onto the conveyor belt and the story, like these publications themselves, would fade into relative obscurity.

In their heyday though, tabloids and so-called "yellow journalism" publications of the mid-to-late-1800s had much greater power and influence over audiences. Pioneers of the form like Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst buffered hard news articles with intentionally exaggerated and sensationalized ones to drive up sales and circulation. It worked brilliantly and the two individually controlled some of the most powerful media companies in the country.

However, there were consequences to this kind of reporting. Many historians point to the yellow press as a significant factor in galvanizing public support for the Spanish-American war.

Today, as print publications draw their final dusty breaths, the rise of the internet and social media have given a new generation of Pulitzers and Hearsts a chance to stake their claim.

TODAY

Increasingly, more and more people are turning to the internet and social media as their primary news source. According to a survey by the Pew Research Center, Americans between the ages of 18-49 are more likely to get their news from the internet rather than TV, radio or print newspapers. But experts warn that this new technology may just create more grass for snake oil salesman to slither through.

"Fake news is a business model," says Dr. Doug Tewksbury, associate professor of communication studies at Niagara University. "Fake news is about advertising. Like all things, when it comes to advertising-supported media, the more people who click on it, the better."

On the web, the term "clickbait" is applied to describe vague or provocative headlines that drive traffic, or clicks, toward a website in order to boost revenue. Scrolling to the bottom of just about any web page will lead you to an eye-catching title designed to get readers to click on it.

This is done for effectively the same reason as their paper printed predecessors: to drive up interest and increase circulation.

This titling practice proved to be so effective that it began to influence many of the mainstream organizations. Today, many craft their online headlines to entice rather than inform.

Compounded with the fact that anyone with an internet connection has the ability to create a professional-looking website, the cosmetic line today between "real" and "fake" news has become blurrier than video footage of Bigfoot, making it harder and harder to distinguish credibility between the two.

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS?

Media and cultural theorists have studied the effects that media have on peoples for decades. While there is a consensus among many modern theorists that media do have effects on people, there are no definitive conclusions as to how extensive those effects can be.

Stanford University published a study in November 2016 (the study began in 2015, long before the election) that found young people, middle-schoolers to college students, were surprisingly inept when it came to identifying whether or not the information they see on social media came from a credible source.

Then in February, Stanford published another study looking into whether the types of fake news stories appearing on social media may have directly swayed voters heading into the polls. Almost paradoxically, this study found that, even though fake stories and posts favoring Trump were shared at nearly quadruple the rate of those favoring Clinton, the number of people who actually viewed those stories was quite small.

But the researchers involved in this study were quick to point out that, while the effects can be mitigated, it would be impossible to say the effects of fake news are inconsequential.

On Dec. 4, 2016, while hungry patrons enjoyed lunch, a 28-year-old man entered the Comet Ping Pong restaurant and pizzeria in Washington, D.C., with an AR-15 rifle and fired shots into the air.

When police later questioned him, he admitted he had been influenced into believing a widespread internet conspiracy known as Pizzagate. Featured on popular conspiracy websites like InfoWars, the theory believes the store's owners and high-profile Democratic leaders were harboring a clandestine child-sex trafficking ring somewhere on the premises.

The conspiracy gained popularity in the months leading up to the election, despite being thoroughly debunked by a number of news organizations and fact-check websites, including the New York Times, Fox News and Snopes.

Upon feeling confident that the local pizzeria was not in possession of exploited children, the man surrendered to police. Unfortunately the story doesn't end there, conspiracy theorists now believe the gunman himself is merely part of a false-flag operation to discredit the theory.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

While some question why social media sites don't block fake news purveyors outright, the problem is a constitutional one. The First Amendment guarantees freedom of speech and the press, meaning attempts of this kind fall into murky legal grounds.

In March, Niagara University held a panel discussion titled "Fake News and Alternative Facts: Are We Living in a Post-Fact World?" It featured a number of media and cultural studies professors. Dr. Kevin Hinkley, instructor of political science and criminal justice at NU, explained how the Sedition Act of 1798, which sought to punish falsehoods propagated against the government, was abused to prosecute people who criticized it at all.

"This sets a dangerous precedent. ... But so far, one that this country has avoided repeating, at least to that scale," he says.

While fake news can't be banned outright, there are ways people can help insulate themselves from it.

When asked which news organizations are most trustworthy, Tewksbury says follow the money.

"The best sources are advertising free ones, because they produce news for different motivations," he says.

Americans seem to agree. Many studies list PBS, NPR and the BBC as among the most trustworthy news sources. But such studies note that how trustworthy a news source is perceived is often tied to how well known they are, as well as viewers' political bias.

The NU panelists agreed the leading reason why people can be duped by misinformation is confirmation bias.

"People consume (news) like they would any other consumer good, in order to mold identity," says Dr. Kenneth Culton, associate professor and chairperson of NU's social sciences program. "When you consume news from one source, you're saying something about yourself, versus another source."

For many media outlets, this has become the model for which business is conducted. Many-larger-scale organizations like Fox News and the Huffington Post regularly spin stories to suit a political narrative in order to attract customers who share those ideas.

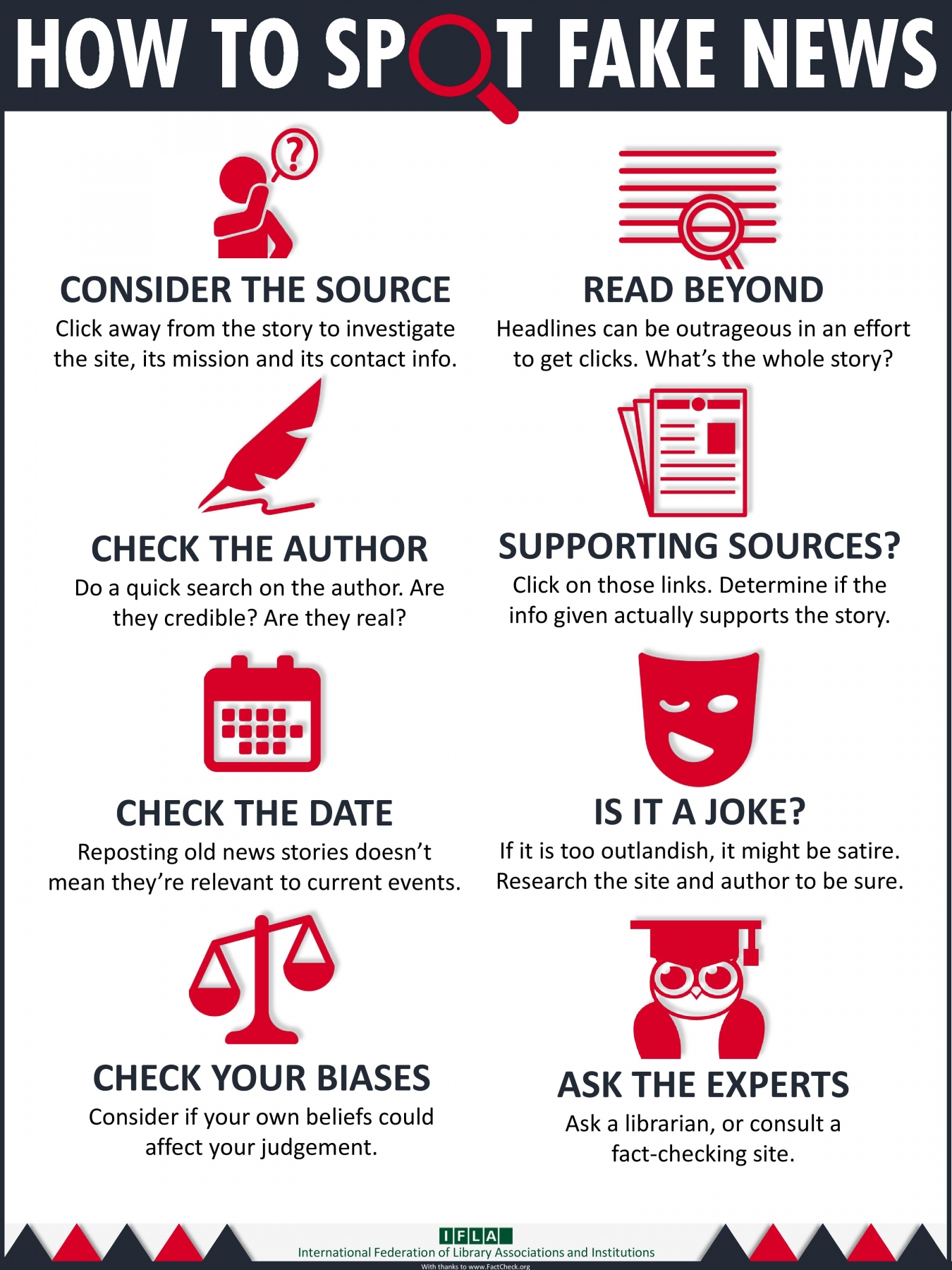

The following info-graphic from the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions is based on information available on Factcheck.org. It offers advice on how to increase media literacy. The sentiments listed here were echoed by Tewkesbury and the panel at NU:

"The question is 'what is real news?' " Tewksbury says. "The best answer we have is evidence-based, highest standards of journalistic practice. ... Good reporting is based on evidence and, if there is no evidence, the speculation is there, highlighting that there is no evidence."

This kind of discipline is what is sorely lacking on the internet and remains one of the biggest contrasts between "fake news" sites and actual journalism. Many purported claims can be swiftly debunked, and whenever a fake news or conspiracy site has their credibility or motives questioned, they usually claim satire or "performance art," thus fully acknowledging both the falsehoods they spread, and their influence.

While there are some who actively seek out and fully trust so-called "alternative news" sites, many are simply swept out by the deep waves of it that exist on the internet.

It's important to acknowledge there are valid reasons why Americans are right to harbor some level of distrust for the mainstream press.

Advertising-supported journalism creates inherent conflicts of interest. In 2011, NBC was widely criticized for failing to report on its parent company, General Electric Co., for paying zero dollars in taxes despite record profits. Fox News and ABC have also been chastised for similar practices.

Further, the media's failure to ask tough questions when the public has needed them the most, like with the events leading up to the war in Iraq, has further damaged their reputation.

There is nothing wrong with being skeptical, in fact it's a good thing. Questioning authority is how common people keep people in power accountable. But there are more intuitive approaches for staying informed than just becoming cynical. Because when cynicism becomes the new normal, real problems can arise.