Featured News - Current News - Archived News - News Categories

Tree removal 'a daunting task'

By Alice E. Gerard

Grand Island is now "ground zero" for the emerald ash borer, said Mark Whitmore, an entomologist from Cornell University.

He was speaking at a public information session on the emerald ash borer, which was held Oct. 4 at Grand Island Town Hall.

The emerald ash borer was first spotted on Grand Island in 2014, near the Nike Base and on West River Road, north of Bedell Road.

According to Patrick Marren, a senior forester with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, who spoke about the insects for an article titled "Tiny Insects Put Island Trees at Risk" in 2014, the infestation was "very small" at that point. Now, said Whitmore, every tree on Grand Island is infested, and many will die.

The removal of dead and dying ash trees could be financially devastating for homeowners and expensive for communities, as well. New York State Sen. Tim Kennedy told the approximately 80 people at the presentation that he had proposed two pieces of legislation to address the problems created by the tiny invasive insect.

The first piece of legislation offers tax credits of up to $100 for people who have ash trees treated and up to $300 for people who have infested trees removed from their property. The second piece of legislation calls for biodiversity when replacement trees are planted.

Metropolitan Detroit has followed a similar practice in replacing trees. In the past few years, 26 species of trees were planted in the Detroit area. In the 1950s, Detroit lost all of its elm trees to Dutch elm disease. The city then replaced the elm trees with ash trees, resulting in another disaster, because only one species was planted.

More than 70,000 city street trees succumbed to the emerald ash borer between 2005 and 2007.

Ash trees comprise approximately 30 to 60 percent of Grand Island's tree population. The potentially devastating effects of an emerald ash infestation on Island trees have been known for some time.

In 2008, David McQuay of the Woodlawn Interpretive Office of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation said the arrival of the emerald ash borer could cause disaster throughout the state and could "devastate state parks along waterways."

New York state has approximately 900 million ash trees.

One year later, on June 15, 2009, Cornell University entomologist Rick Hoebeke made the first Western New York sighting of an emerald ash borer, in Randolph, in Cattaraugus County. The first Erie County infestation was in Lancaster in 2011. That discovery was actually made by accident.

"An emerald ash borer landed on an arborist's clipboard," Whitmore said.

The emerald ash borer travels quickly. "They are strong flyers," Whitmore said, adding that an emerald ash borer can fly 20 miles in a day. The insects can also travel by attaching themselves to car windshields.

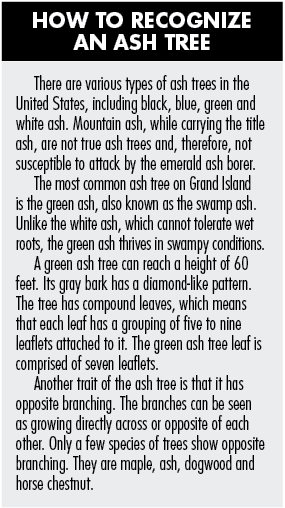

Dead and dying ash trees can now be seen all over Grand Island. One of the first visible signs is the loss of the tree's top foliage. Another sign of an infestation is brown spots on the trunk. This indicates that woodpeckers have been foraging.

"Woodpeckers are the best indicators" of an emerald ash borer infestation, Whitmore explained.

Other signs of infestation include the reduction in the size of the leaves and the growth of suckers from all over the trunk. Suckers normally grow from the bottom of the trunk and have to be pruned off of the tree. This unusual growth of suckers is called "epicormics sprouting."

The emerald ash borer, in its larval state, destroys ash trees from the inside. After the adult lays its eggs on the tree, the larva eats the tree's inner bark. That disrupts the tree's ability to transport nutrients throughout the tree. Within two to three years of infestation, the tree is dead.

Whitmore said that the dead and dying trees pose an imminent threat to the community's infrastructure.

"We need to protect ourselves and our infrastructure," Whitmore said. The bark of a dead ash tree is brittle and branches could break off or the entire tree could fall. The trees could fall on houses, cars, pedestrians or power lines.

"I live in the country near Ithaca and I have a chainsaw in the truck and a generator," Whitmore said.

Diane Evans, chair of the Conservation Advisory Board and a member of the Grand Island Emerald Ash Borer Task Force, said, "This is a sad occasion. We all love our trees. The town has a huge job. It has to take down dead trees and clean up debris."

Deputy Highway Superintendent Dick Crawford, who serves as chair of the Grand Island Emerald Ash Borer Task Force, said of the town is doing an inventory trees in its right of ways.

"The focus is on the health, safety and welfare of the community. This will be a daunting task," he said.

Whitmore has "studied bugs that eat trees for almost 40 years. It was fun. I never imagined that we would face this situation with insects."

He said that he advocates using insecticides to save "magnificent individuals."

Whitmore added that it is important to save the genome. There are federal, state and regional programs in place to save seeds from ash trees.

The goal, he said, is to cross the American ash tree species with Asian ash tree species, which are resistant to the insect. This technique has been successful with the American chestnut, which was the victim of a blight that began in the early part of the 20th century. A hybrid chestnut was developed and has been planted. The development of a hybrid ash species is a long-term goal, Whitmore said.

A more short-term method of saving ash trees is for a certified arborist to inject them with a systemic insecticide, either in the fall or in the spring. Whitmore said that the most effective of the systemic insecticides is Tree-age.

"You want to find a tree that still looks good. Call an applicator in the spring. By next fall, the number of trees that can be treated will drop dramatically," Whitmore said.

The injection is effective for three years. After that, another application will be needed. Whitmore said people who save trees must be prepared to treat the trees aggressively for 12 years.

To treat the trees more effectively, damp ground is necessary. "This was a bad year for treating trees because of the drought," Whitmore said.

"Our big trees will die," he said. "We don't know why certain trees have survived. The surviving trees are worth gold. I like preserving magnificent individuals with systemic insecticides."

Marren, a member of the Western New Emerald Ash Borer Task Force, described efforts being made to contain the emerald ash borer. One of these efforts involves firewood restrictions.

"There is a 50-mile limit for moving firewood," Marren said.

He explained sellers have to provide customers with documentation of the firewood. The emerald ash borer quarantine in New York follows transportation corridors, such as the New York State Thruway, Marren said.

Other insects to be on the lookout for are the hemlock wooly adegid, which kills both hemlock and spruce trees, and the Asian longhorned beetle, which targets maple trees.